Bonsai, Kunst und Kimura

Bonsai, Art and Kimura

Von / by Gunter Lind

Man kann die Geschichte von Bonsai ganz grob in drei Phasen einteilen - nicht als

strenge zeitliche Abfolge, sondern eher als drei unterschiedliche Einstellungen zu Bonsai, die Rückwirkungen auf die Art und Weise der Gestaltung hatten. Mit plakativen Begriffen könnte man sie

bezeichnen als:

1. Bonsai als Brauchtum, die religiöse und mythische Einstellung,

2. Bonsai als Design, die kunsthandwerkliche Einstellung,

3. Bonsai als Kunst, die künstlerische Einstellung.

The history of bonsai can roughly be divided into three phases – not as a strictly delimited chronological sequence, but rather as different approaches that had an influence on the way of shaping bonsai. In a slightly exaggerated way they could be characterized as follows:

1. Bonsai as tradition, the religious / mythical approach,

2. Bonsai as design, the craft approach,

3. Bonsai as art, the artistic approach.

1. Die Ursprünge von Bonsai liegen wohl im Religiös-Mythischen. Vorläufer waren vielleicht im Totenkult des alten China verwendete Gefäße in der Form einer der Inseln der Seligen, ein steiler Berg mit vielen Grotten und Höhlen, der aus dem Meer herausragt. Daraus entstanden die ersten Paradieslandschaften in der Schale: aus Steinen geformte Berge, bepflanzt mit Moos, kleinen Bäumchen und anderen Pflanzen. DieVorstellung von den Inseln der Seligen verband sich mit manchen anderen Gedanken aus der Welt des Mythos, die der Landschaft oder dem Baum in der Schale eine symbolische, über den ästhetischen Aspekt hinausreichende Bedeutung verliehen. Diese Einstellung zu Bonsai hat sehr lange eine Rolle gespielt. Noch Ende des 19. Jhs. dürften die meisten Bonsai in japanischen Haushalten nicht primär aus ästhetischen Gründen angeschafft oder verschenkt worden sein, sondern als Glücksbringer zu verschiedenen Anlässen, zu Neujahr, zur Hochzeit oder einfach um Jemandem ein langes Leben und Wohlstand zu wünschen. Selbstverständlich hat das eine ästhetisch ansprechende Gestaltung nicht verhindert, aber sie war nicht das einzige Ziel. Die Neujahrs-Ume hatte auch ihren Wert, wenn sie nicht optimal gestaltet war, Hauptsache sie blühte zu Neujahr.

The origins of bonsai are said to be religious, mythic. The predecessors of the art might have been containers used in the chinese death cult that were shaped like one of the islands of the blessed, a mountain steeply protruding from the sea, with many grottos and caves. The next stage were the first paradise landscapes in a pot: mountain-shaped stones planted with moss, tiny trees and other plants. The imagination of the islands of the blessed combined with other mythic thoughts gave a symbolic meaning to the landscape or tree in the pot, well beyond the aesthetic aspect. This approach to bonsai prevailed for a long time. Even at the end of the 19th century most bonsai were not bought or given to others primarily for aesthetic reasons but as a lucky charm for different occasions like new year’s day, a wedding or simply to express one's wishes of long life and prosperity. Of course this did not prevent an aesthetically appealing design, but it was not the primary intention. The new year Ume had its value, even if it was not designed perfectly, the most important thing was that would blossom at new year.

2. Ein Bonsaigewerbe entwickelte sich in Japan im 18. Jh., zunächst als Teil des Geschäftsbereichs "Gärten und Blumen". Im 19. Jh. gab es jedoch bereits spezialisierte Bonsaibaumschulen, jedenfalls für die hauptsächlich nachgefragten Arten, die Kiefer und die Ume. Ihre Ware bestand nicht aus Kunstwerken, sondern aus standardisiert angezogener Baumschulware. Hier liegen die zunächst noch recht bescheidenen Wurzeln des kunstgewerblichen japanischen Bonsai, der später den Siegeszug um die Welt antreten sollte. Charakteristisch für die kunsthandwerkliche Bonsaitradition ist eine gewisse Standardisierung des Formenrepertoirs und der Versuch, die Gestaltung jeder einzelnen Form weitgehend durch Regeln festzulegen. Das sind allerdings Charakteristika, die bis zu einem gewissen Grad wohl für jede Art von Kunsthandwerk gelten. Für die dekorative Kunst Japans, einschließlich der Gartenkunst, sind sie jedoch besonders typisch. Die regelgerechte Ausführung eines Werkes gemäß den Idealen einer bestimmten Schule wird sehr hoch geschätzt. Dem wohnt ein gewisser Hang zur Perfektion inne. Nicht zufällig hat Japan gerade auf dem Bereich der dekorativen Kunst hervorragende Leistungen aufzuweisen.

In den Regeln ist auch der Ausdrucksgehalt einer bestimmten Bonsaiform festgelegt. So soll etwa die klassische Kiefer einen männlich-kraftvollen und kompakten Ausdruck besitzen, die Ume sollte ursprünglich ein locker-übersichtliches Astwerk besitzen, auf dem die Blüten wie einzelne Schneeflocken wirkten. Das Beispiel der Ume zeigt, dass solche Regeln und Gestaltungsideale der Mode unterworfen sind. Die moderne Ume ist deutlich kompakter geworden und hat Elemente des klassischen Kiefern-Designs aufgenommen. Solche Entwicklungen sind jedoch langfristige Trends. Sie eröffnen dem Gestalter kaum individuelle Spielräume. Überhaupt sind weder der formale Aspekt noch der Ausdrucksaspekt in der kunsthandwerklichen Tradition besonders geeignet, einen Bonsai aus der Menge der regelgerechten herauszuheben. Wer sich gegenüber der Konkurrenz auszeichnen möchte, dem bleibt eigentlich nur ein Weg, derjenige der Perfektion. Beim Bonsai zeigt sich diese Perfektion nicht nur in der vollkommenen Beherrschung der Regeln, sondern vor allem darin, dass man davon am reifen Werk nichts mehr sieht. Der vollendete kunsthandwerkliche Bonsai wirkt in seiner formalen Perfektion und im hohen Grad seiner Verfeinerung sowohl extrem künstlich als auch in gewisser Weise natürlich, wenn man dies Wort in seiner zweiten Bedeutung verwendet: er wirkt, als sei er selbstverständlich so wie er ist, als könne er nicht anders aussehen.

In the 18th century a bonsai trade developed in Japan, at first as a part of the gardens and flowers industry. In the 19th century there were already specialised bonsai nurserys which produced the mainly requested species, pine and ume (flowering apricot). Their merchandise were no pieces of art but nursery stock produced according to certain standards. These were the humble roots of the Japanese craft bonsai which later went on its triumphal progression around the world. It is a typical feature of the craft approach that the repertoire of shapes was standardized and there were rules for their design. To a certain degree, this might apply to all kinds of craft. For the decorative arts of Japan however, including the art of gardens, they are especially typical. The regular implementation of works according to the ideals of a certain school is highly appreciated. This implies a certain degree of perfectionism. It is not coincidental that Japan has achieved extraordinary accomplishments in the field of decorative art.

The rules also pertain to the expressive features of a certain bonsai style. For example, a classic pine was supposed to have a powerfully masculine and compact expression, and a Ume should have a sparse, informal ramification on which the flowers look like scattered snow flakes. The example of the ume tells us that rules and design ideals are subject to fashions. The modern ume is much more compact and has adopted elements of the classic pine design. Such developments however are long-term trends. They leave almost no creative freedom to the designer. Moreover, neither the formal nor the expressive aspect in the craft tradition is particularly suited to raise a bonsai above the masses of just 'correct' trees. For a designer who would like to stand out from the crowd, the only way to do this is via perfection. On bonsai, this perfection doesn't only show in the perfect application of the rules, but in the fact that this doesn't show in the finished piece. The perfect craft bonsai, in its formal perfection and high degree of refinement, looks both extremely artificial and at the same time perfectly natural, if this word is taken in its second meaning: it looks self-confident, as if it couldn't have been different.

3. Bonsai als Kunst? Vielleicht hat es schon seit sehr langer Zeit Bonsai gegeben, die von ihren Gestaltern als Kunstwerke gemeint waren. Seit in der Song-Zeit der Einzelbaum-Bonsai erfunden wurde, haben chinesische Literaten-Beamte Bonsai gestaltet, und sie haben sich als Künstler begriffen. Allerdings war ihr Kunstbegriff an der Kalligraphie und der Tuschmalerei orientiert. Als wesentliches Kriterium für die Eigenständigkeit der künstlerischen Leistung galt die individuelle, unverwechselbare Pinselführung, während das Sujet und sein Ausdrucksgehalt gern der Tradition entnommen wurden. Es gab kein Bedürfnis nach Innovation, keinen Stilwandel im europäischen Sinn. Auf Bonsai ist dies kalligraphische Kunstverständnis nicht so leicht übertragbar. Worin sollte die Individualität des Gestalters sich ausdrücken, wenn man in Form und Ausdruck der Tradition folgte? Vielleicht haben die Literaten ihre Bonsai doch nicht als vollwertige Kunstwerke betrachtet, sondern nur als Schmuck des Gartenpavillons oder des Studios?

Wie dem auch sei - jedenfalls scheint erst in jüngster Zeit von Bonsaigestaltern der explizite Anspruch erhoben zu werden, als bildende Künstler zu gelten und Kunstwerke zu schaffen. Meine These ist, dass diese Haltung nicht aus der japanischen Bonsaitradition allein erwachsen ist, sondern dass sie dort erst mit der Übernahme eines westlichen Kunstbegriffs entstehen konnte. Vor einigen Jahren gab es eine Kunstausstellung mit dem Titel "Kunst ist Innovation". Dies ist für die neuere europäische Kunst charakteristisch. Schon bei Karl Friedrich Schinkel liest man: "Überall ist man nur da wahrhaft lebendig, wo man Neues schafft - überall, wo man sich ganz sicher fühlt, hat der Zustand schon etwas Verdächtiges..." Der traditionellen fernöstlichen Kunst ist diese Haltung fremd. Sie definiert Kreativität eher als virtuoses Spiel mit den Traditionen, denn als Schöpfung des Neuen.

Bonsai as an art? Perhaps there have been always been bonsai which were intended as pieces of art by their creators. Since the invention of the "single tree bonsai" in the Song-era, chinese littérateurs-officials have created bonsai and they thought of themselves as artists. However their idea of art was influenced by calligraphy and brush painting. There the most important criterion for the originality of the artistic achievements was the individual, distinctive use of the brush, while the subject and its expressive content was often just taken from the tradition.There was no wish for innovation, no change of style which is so central to the European concept of art. It is not so easy to transfer these artistic concepts from calligraphy to bonsai. How should the individuality of the designer be expressed, if shape and expression was determined by tradition? Perhaps the literati didn't regard their bonsai as pieces of art after all, but just as decoration for their garden pavilions or studios?

Be this as it may, it seems that bonsai designers only recently started to explicitly claim the status of artists and their works to be pieces of art. My claim is that this attitude didn't originate from the Japanese bonsai tradition alone, but that it could only arise with the adoption of Western art concepts. A few years ago there was an exhibition with the title "Art is Innovation" - this is characteristic of the newer Western art. Already Karl Friedrich Schinkel, a German architect of the early 19th century, wrote: "Everywhere you're only truly alive where you create something new. Whenever you're sure of something, this is a suspicious thing ..." This attitude is alien to traditional Asian art, where creativity means more a virtuous play with traditions than creating something new.

1 - Masahiko Kimura

Dieser neue Begriff von Bonsai als Kunst ist mit dem Namen Masahiko Kimuras verknüpft. Er hat mit seinen Werken demonstriert, dass Bonsai tatsächlich Kunst sein kann und er hat auch eindeutig ausgesprochen, dass er sich als Künstler im beschriebenen Sinn betrachtet. Er drückt verschiedentlich den Stolz aus, Bonsai geschaffen zu haben, die in der Geschichte ohne Vorbild sind, und er reklamiert eindeutig den Primat der Kreativität über die Tradition. Gerade auch dort, wo Kimuras Kreationen auf Ablehnung gestoßen sind, hat man nie bezweifelt, dass sie tatsächlich etwas Neues darstellen und damit indirekt seinen Anspruch anerkannt. Die Ablehnung richtete sich vielmehr gegen die Innovation als solche, zielte also auf die Bewahrung der kunsthandwerklichen Tradition.

This new definiton of bonsai as art is linked to the name of Masahiko Kimura. He demonstrated with his works that bonsai really can be art, and he clearly articulated that he thinks of himself as an artist in the sense just described. He often expresses his pride to have created bonsai that don't have a model in history, and he definitely claims the primacy of creativity over tradition. Especially in those cases where Kimura's creations met criticism, it was never questioned that they really were something novel and thus indirectly affirmed his claims. This criticism was aimed at innovation as such, its goal was to preserve the craft traditions.

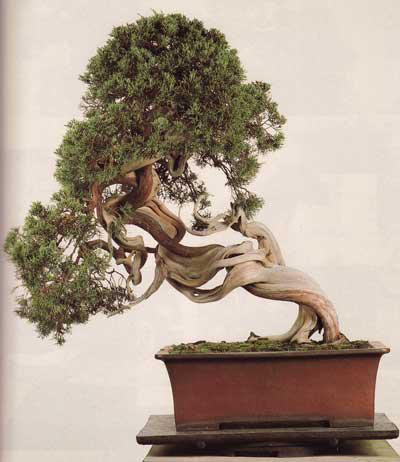

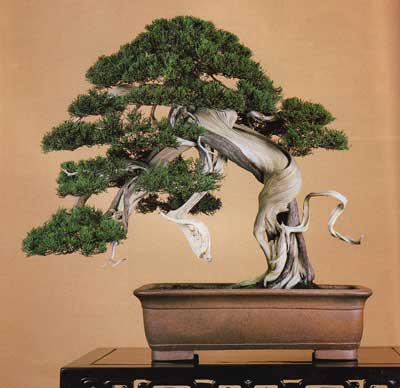

2 - Chinesischer Wacholder / Chinese juniper (Juniperus chinensis), Höhe: 78 cm (30 1/2 in)

Was ist das Neue an Kimuras Bäumen? Es dürfte Konsens herrschen, dass das auffälligste Charakteristikum die Dominanz des Totholzes ist. Dieses wird in sehr freier Form bearbeitet. Kimura benutzt selbst den Begriff Bildhauerei. Bild 2 zeigt einen berühmten Baum Kimuras. Es ist sicher nicht übertrieben, wenn man behauptet, dass dieser Baum die Entwicklung des modernen künstlerischen Bonsai maßgeblich beeinflusst hat. Die Form des Stammes ist höchst komplex, detailreich und bewegt, dabei kraftvoll und kompakt. Zwar bevorzugt Kimura Rohmaterial, das bereits interessante Totholzformen besitzt; aber wenn das nicht der Fall ist, kann auch eine Skuptur entstehen, die mit dem ursprünglichen Stamm keinerlei Ähnlichkeit mehr hat. So kann ein schlichter, zylindrischer, oben abgesägter Stamm zu einer filigranen Skulptur ausgearbeitet werden.

What is new about Kimura’s trees? People would probably agree that the dominating deadwood is the most striking feature. This is shaped very freely. Kimura himself uses the word sculpturing. The above picture shows a famous tree of Kimura. It is no exaggeration to say that this tree has had a great influence on the development of modern artistic bonsai. The shape of the trunk is highly complex, rich in details and movement, at the same time powerful and compact. Although Kimura prefers raw material which already has interesting deadwood, if this is not the case, he can also create a sculpture which bears no resemblance with the original trunk. In this way, a plain cylindric trunk that was cut off at the top can be worked into a finely wrought sculpture.

3 - Japanische Eibe / Japanese yew (Taxus cuspidata)

Gegenüber dem interessanten, filigranen, abwechslungsreichen Totholz erscheint die

lebende Krone des Bonsai eher als weniger wichtiges Beiwerk. Sie ist oft klein, in den Formen eher einfach und geschlossen und oft auch ganz traditionell gestaltet. Sie bildet einen deutlichen

Kontrast zu dem komplexen Formenreichtum des Totholzes.

In contrast to the interesting, sublte, complex deadwood, the living crown of the bonsai often seems to be less important. In many cases it is small, has a simple compact shape and is also designed very traditionally. It stands in strong contrast to the complex shapes of the deadwood.

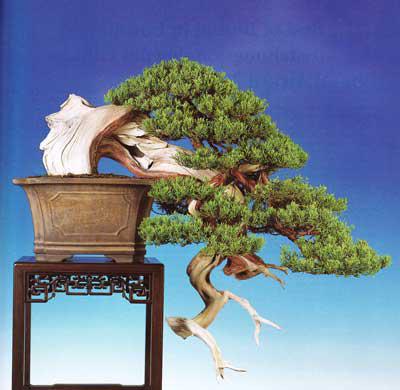

4 - Chinesischer Wacholder / Chinese juniper (Juniperus chinensis)

Wenn man genauer hinschaut, erkennt man allerdings, dass die Einfachheit der Krone

oftmals bloß vorgetäuscht ist. Sie hat manchmal nicht die einfache Aststruktur, die man dahinter erwartet, sondern ist durch phantasievolles Biegen eines einzigen, oder weniger Äste entstanden.

Um solche, im vorliegenden Material nicht angelegte Formen verwirklichen zu können, hat Kimura neue, drastische Gestaltungstechniken entwickelt, besonders für Wacholder. Da wird die Lebensader

vom Stamm abgelöst und beide Teile werden gänzlich unabhängig voneinander behandelt. Im Extremfall wird der Stamm direkt über dem Erdniveau durch Heraussägen eines Stammteiles eingekürzt. Die

dort übrigbleibende Lebensader wird aufgewickelt und unter der Erde versenkt.

On a closer look however you can see that the simplicity of the crown is just appearance. It doesn't have the simple branch structure you might expect, but has been created by imaginative bending of only one or a few branches. In order to be able to create such shapes that were not originally present the material, Kimura has developed new, drastic design techniques, especially for junipers. The live vein might be separated from the trunk and both parts treated completely independently. In extreme cases, the trunk is shortened by chopping out a piece of trunk just above the soil level. The remaining live vein is then coiled up and hidden beneath the surface of the soil.

5 - Chinesischer Wacholder / Chinese juniper (Juniperus chinensis)

Verbunden mit dem Anspruch auf Freiheit des Ausdrucks, auf uneingeschränkte

Kreativität, ist ein Aufgeben des traditionellen Axioms, dass die Natur Vorbild der Bonsaigestaltung sei. Auch wenn das Naturvorbild in sehr verschiedener Form ausgelegt wurde, wenn der Baum

manchmal mehr symbolisiert als dargestellt wurde, es blieb jedoch stets ein Baum. Bei Kimura hat man jedoch manchmal den Eindruck, dass der Bonsai nicht mehr in erster Linie Baum ist, sondern

Anlass zur Kunst. Der Baum wird nicht mehr dargestellt, symbolisiert, interpretiert oder was auch immer. Er wird zur Skulptur, zum modernen Kunstwerk und es ist dann relativ gleichgültig, dass es

sich um einen Baum handelt. Dazu passt, dass auch die klassischen Gestaltungsregeln weitgehend ihre Gültigkeit verlieren. Sie sind für Bäume formuliert worden und treffen für die modernen

Plastiken teilweise gar nicht mehr zu. Diese Bäume haben kein klassisches, gleichmäßiges Nebari, ob Äste als gegenständig zu gelten haben, läßt sich oft gar nicht entscheiden und Überkreuzungen

sind beim Totholz ein dekoratives Element.

Linked to this claim of freedom of expression and unlimited creativity is a dismissal of the traditional axiom that nature should be the example for bonsai creation. Even if nature's example had been interpreted in many different ways, even if a tree sometimes was more a symbol than a representation of nature, a tree still remained a tree. With Kimura's work you sometimes have the impression that the bonsai isn't primarily a tree, but an occasion for creating art. The tree doesn't depict, symbolize, interpret - it becomes a sculpture, a modern work of art, and in fact it doesn't matter any more if it's a tree. Consistent with this is the dismissal of the classic rules of design - they had been formulated for trees and might not apply to sculptures at all. The trees don't have a classic, uniform nebari, it is often impossible to decide if there are bar branches, and crossing parts become a decorative element in the deadwood.

6 - Chinesischer Wacholder / Chinese juniper (Juniperus chinensis)

Überkreuzungen sind beim Totholz ein dekoratives Element.

Crossing parts are a decorative element on deadwood.

7 - Der Baum, Anlass zur Kunst? The tree - a medium for creating art?

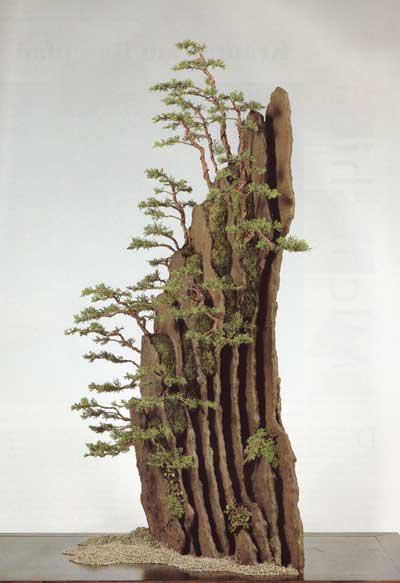

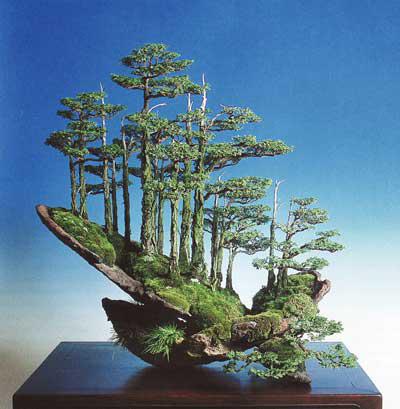

8 - Chinesischer Wacholder auf Fels / Chinese juniper on rock

Dem widerspricht nicht, dass Kimura verschiedentlich betont hat, er wolle natürliche Bonsai schaffen. Sein Begriff von Natürlichkeit entspricht ganz demjenigen der künstlerischen Tradition des fernen Ostens, und hat mit europäischem Naturalismus nichts zu tun. Es geht dabei nicht um die Erscheinungen, sondern um das Wesen der Dinge. Der Bonsai soll nicht so aussehen wie ein Baum, ihn nicht darstellen oder symbolisieren; er soll vielmehr ähnliche Emotionen wecken wie ein Baum aus der Wildnis. Er soll die Größe, die Wildheit, die Dynamik, das Dramatische der Natur ausdrücken.

It is no contradiction that Kimura has often stressed that he aims to create natural bonsai. His concept of naturalness is that of the Asian art tradition and not related to Western Naturalism. It is not about appearances, but about the nature of things. A bonsai is not supposed to look like a tree, to represent or symbolize it; it should give us emotions that are similar to the ones created by a tree in nature. It should express the greatness, wildness, the dynamic and dramatic aspects of nature.

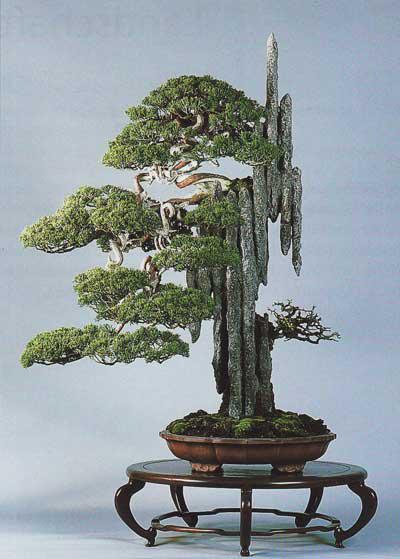

9 - Chinesischer Wacholder / Chinese juniper (Juniperus chinensis)

10 - Ajan-Fichte / Ezo spruce (Picea jezoensis)

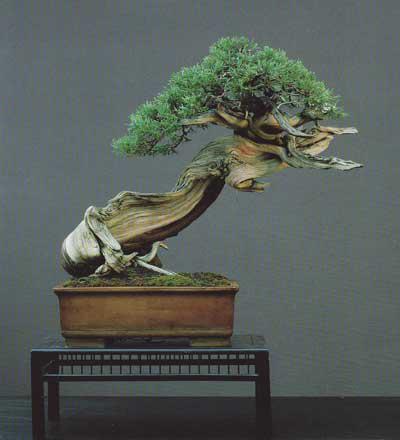

Nicht nur hier zeigt sich Kimuras Verwachsensein mit fernöstlichen künstlerischen Traditionen. Er ist nicht der "Rebell vom Dienst", sondern in vieler Hinsicht der Tradition verpflichtet, auch der klassischen, kunsthandwerklichen Bonsaigestaltung. Nicht nur, dass er auch hervorragende Bonsai in klassischen Formen gestaltet hat und traditionelle, eher chinesisch beeinflusste Landschaften. Selbst seine so neuartig erscheinenden Totholzkreationen haben klassische Wurzeln. Man kann sie als Beispiele der Treibholzform verstehen, die zwar in Japan nie sonderlich beliebt war, aber in China gepflegt wurde. Jedoch gibt es da einen qualitativen Unterschied. Bei der Treibholzform erscheint der Stamm des Baumes gewissermaßen mit Totholz dekoriert, er findet seine Vorbilder durchaus in der Natur, an Grenzstandorten, wo Bäume durch Wind und Wetter gegerbt wurden. Bild 11 zeigt einen Wacholder, der von Kimura in der Treibholzform gestaltet wurde. Die Lebensader ist von der Ansichtsseite kaum zu erkennen, der elegante Stamm erscheint im reinen Weiß des Totholzes. Der Baum strahlt eine klassische Harmonie aus. Der Stamm ist hier noch ein Stamm und keine lebende Skulptur. Aber die Entwicklung dorthin verläuft ohne Traditionsbruch. Vieles ist in der traditionellen Treibholzform schon angelegt. Trotzdem resultiert diese Entwicklung in einer radikalen Veränderung des Ausdrucksgehalts des Bonsai. Zu den klassisch-harmonisch gestalteten Bäumen, bei denen selbstverständlich auch das Totholz konstitutiv sein kann, treten dynamisch-expressive Bäume hinzu und diese Bäume sind antiklassisch.

This is not the only aspect showing that Kimura is deeply rooted in Asian artistic traditions. He is not the eternal rebel but is in many aspects committed to tradition, even to the classic craft oriented bonsai approach. Not only has he created excellent classically shaped bonsai and traditional landscapes influenced by Chinese examples. Even his deadwood creations which seem so new and different have classic roots. One could view them as examples of the driftwood style which was never very popular in Japan, but more so in China. However, there is a qualitative difference. A tree in the driftwood style appears do be decorated with deadwood, and it does have models in nature, such as at extreme locations where trees are battered by the wind and other impacts of the weather. Picture 11 shows a juniper that Kimura shaped in the driftwood style. The live vein can hardly be seen from the front side, the elegant deadwood trunk shines brightly white. The tree is of classic harmony. The trunk is still a trunk and no living sculpture. But the development to that point happens without a breach of tradition. Many things are already contained in the traditional driftwood style. But still this development results in a radical change of the bonsai’s expression. The classically styled harmonic trees which of course can possess deadwood as part of the design are joined by dynamic, expressive trees which are anti-classic.

11 - Chinesischer Wacholder / Chinese juniper (Juniperus chinensis) mit Totholzstamm / with deadwood trunk (Shari)

12 - Hinoki-Scheinzypressen / Hinoki false cypresses (Chamaecyparis obtusa), Felsenform / clinging to a rock

Inzwischen hat Kimura viele Nachahmer gefunden, nicht nur in Japan, sondern gerade auch in Europa. Und ich meine damit nicht nur, dass Totholz modern geworden ist. Mindestens genau so wichtig erscheint mir die veränderte Sichtweise auf Bonsai, die mit dem Übergang von der kunsthandwerklichen zur künstlerischen Bonsaigestaltung verbunden ist. Bonsai ist dynamischer, expressiver geworden. Die Begegnung mit den Totholzskulpturen hat auch unsere Sichtweise auf Bonsai überhaupt verwandelt.

Meanwhile Kimura has been copied a lot, not only in Japan, but also and especially in Europe. This doesn't only mean that deadwood has become fashionable. Even more important has been a change in the perception of bonsai, a change from bonsai as a craft to bonsai as an art. Bonsai has become more dynamic and more expressive. The encounter with deadwood sculptures has changed our perception of bonsai in general.

Francois Jeker (Ästhetik und Bonsai, übers. von Karin Landsrath, Eigenverlag 2000) hat versucht , ästhetische Kriterien für die moderne Bonsaigestaltung aufzuzeigen. Es geht ihm dabei nicht speziell um den Stil Kimuras, sondern um die ästhetische Weiterentwicklung des klassischen Stils überhaupt. Unter seinen Kriterien sind solche, die auch die Gestaltung im klassischen Stil schon geleitet haben, wie Asymmetrie, Verwendung von Leerräumen oder die Erreichung von Räumlichkeit. In unserem Zusammenhang sind jene Kriterien interessanter, die zwar auch im klassischen Stil bereits Gültigkeit hatten, die jetzt jedoch in charakteristischer Weise uminterpretiert werden. Das gilt besonders für das Konzept der Einheit. Es ist Andy Rutledges "design integrity" sehr ähnlich. Allerdings wählt Jeker in dem Spektrum zwischen Harmonie und Interessantheit eindeutig den zweiten Pol. Ihm erscheint nur der interessante Bonsai schön: Die Schönheit ist rebellisch, unverschämt und subversiv. Dann ist die Vermeidung aller Inkongruenzen kein Gestaltungsziel mehr. Im Gegenteil: Kontrast und Rhythmus werden zu wichtigen Gestaltungskriterien. Gleichgewicht wird jetzt ausdrücklich als dynamisches Gleichgewicht aufgefasst. Die klassische Ruhe und Harmonie gilt als statisch und wenig ausdrucksstark. Angestrebt werden demgegenüber Dynamik, Bewegung, Ausdruckskraft, Dramatik, und diese Eigenschaften zeigen sich vor allem in der Totholzgestaltung. Ein Beispiel eines europäischen Gestalters möge diesen modernen, expressiven Stil verdeutlichen. Bild 13 zeigt einen in der Treibholzform gestalteten Bonsai von Walter Pall. Der Vergleich mit dem in der gleichen Form gestalteten Baum von Kimura (Bild 11) macht den Unterschied deutlich. Kimuras Baum ist klassisch, ausgewogen, schön. Palls Baum ist ausdrucksstark, dramatisch, für den an die klassischen Formen gewohnten Betrachter tatsächlich etwas "unverschämt".

Francois Jeker (“Bonsai Aesthetics”, published in 2000) tried to elaborate on aesthetic criteria for modern bonsai creation. His subject is not primarily the style of Kimura but the aesthetic advancements of the classic style in general. Some of his criteria are the same that governed the classic bonsai style, such as asymmetry, the use of negative space or the three-dimensionality of the resulting image. For us, however, it is more interesting to look at criteria that were already valid in the classic style but are now re-interpreted in a characteristic way. This applies especially to the concept of unity. It is very similar to Andy Rutledge's principle of “design integrity”. Jeker however, when having the choice between harmony and originality, clearly leans towards the latter. For him, only an original bonsai is beautiful: beauty is rebellious, impertinent and subversive. Avoiding everything inappropriate is not a design goal any more. On the contrary: contrast and rhythm become important criteria of design. Balance is now explicitly understood as a dynamic balance. Classic tranquility and harmony are dismissed as static and less expressive. Instead, the goals are dynamics, movement, expressiveness and dramatic effects, and these qualities are primarily manifested in the treatment of deadwood. Let me use the example of a European bonsai designer to explain this modern expressive style. Image 13 shows a driftwood style bonsai by Walter Pall. When comparing it to Kimura’s tree (image 11) that is shaped in the same style, there are obvious differences. Kimura’s tree is a classic tree, well-balanced, beautiful. Pall’s tree is expressive and dramatic. For a viewer used to classic shapes it really is a bit "impertinent".

13 - Rocky-Mountain-Wacholder / Rocky Mountain juniper (Juniperus scopulorum), von / by Walter Pall, Höhe / height: 60 cm (23 1/2 in)

Bei aller Bewunderung für Kimura und seine Nachfolger möchte ich doch mit einigen eher skeptischen Bemerkungen schließen. Die Entwicklung zum künstlerischen Bonsai bedeutet auch eine Vergrößerung der Kluft zwischen dem Bonsai-Hobbyisten und dem Profi. Unter dem kunsthandwerklichen Paradigma konnte der Hobbyist dem Profi noch nacheifern und gute Gestaltungen erreichen, mochte auch der letzte, professionelle Schliff fehlen. Unter dem künstlerischen Paradigma wird dies die seltene Ausnahme bleiben. Es erfordert eine langjährige Schulung des künstlerischen Blicks und Vervollkommnung der einschlägigen Gestaltungstechniken. Das heißt auch, dass der Profi nicht mehr in erster Linie gärtnerischer Profi sein wird, sondern berufsmäßiger bildender Künstler. Dieser Beruf setzt aber einen Kunstmarkt voraus und einen solchen gibt es bislang höchstens in Japan. In Europa fehlt bisher der Sammler künstlerischer Bonsai, der seine Sammlerstücke professionell pflegen und für Ausstellungen vorbereiten lässt. So kommt es zu der paradoxen Situation, dass manche Bonsaikünstler von Seminarveranstaltungen für Bonsai-Hobbyisten leben und so die Illusion befördern, Kunst und Hobby seien doch noch irgendwie von gleicher Art.

Despite my admiration for Kimura and his followers, I would like to close with some skeptical remarks. The development towards more and more artistic bonsai has led to an increasing gap between bonsai hobbyists and professionals. Under the craft paradigm the hobbyist could emulate the professional’s work and arrive at fine creations, even if the very last professional touches were missing. Under the artistic paradigm, this will be a rare exception. It takes a longterm training of the artistic eye and perfection of the relevant design techniques. It also means that the professional will not be a professional horticulturist, but a professional artist. This profession requires a market for art, and so far such a market exist only in Japan if at all. In Europe there are virtually no collectors of artistic bonsai who let professionals care for them and prepare them for exhibitions. This creates the paradox situation that some bonsai artists live on workshops for bonsai hobbyists and thereby nurture the illusion that art and hobby were of the same kind.

14 - Hinoki-Scheinzypressen / Hinoki false cypresses (Chamaecyparis obtusa), Felsenform / clinging to a rock

Prof. Dr. Gunter Lind

Am 9.4.07 starb Prof. Dr. Lind nach schwerer Krankheit. In der Zeit seines Ruhestandes widmete er sich hingebungsvoll der Erforschung der Bonsaigeschichte. Nur ein sehr kompetenter Bonsai- und Kunstkenner ist in der Lage, ein im Westen so noch völlig unbekanntes Wissensgebiet, aufzuzeigen.

Viele seiner Artikel wurden zum Beispiel in BONSAI-ART und im BONSAI-FACHFORUM veröffentlicht, und viele noch unvollendete Artikel werden wohl leider für uns im großen Arkanum verschlossen bleiben.

Zur Vollendung der „The World of the Pots“-Seite ist es eine Ehre, diesen Artikel hier zeigen zu dürfen.

Mein ganz besonderes Dankeschön an Frau Lind.

Copyright: Gerlind Lind

On the 9th of April 2007, Prof. Dr. Lind died after a severe illness. After his retirement, he had dedicated most of his time to the exploration of bonsai history. It took a very competent bonsai and art connoisseur to disclose a field of knowledge that is so completely unknown in the west.

Many of his articles were published by the magazine BONSAI ART and in the German BONSAI FACHFORUM internet forum. Unfortunately many unfinished articles will be lost for us.

It is a great honor to be able to publish the article on this web site.

My special thanks to Mrs Lind.

Copyright: Gerlind Lind

Herzlichen Dank auch an BONSAI ART für die großzügige Bereitstellung der Fotos von Kimura und seinen Bäumen, - so wie auch an Walter Pall für die Bereitstellung seines Fotos.

Special thanks also to BONSAI ART for kindly providing the photographs of Kimura and his trees, and to Walter Pall for providing his photograph.

Translation: Heike van Gunst