Tokoname

Der Name einer Stadt steht für Bonsaischalen

A City That Has Become Synonym For Bonsai Pots

Wenn man von Tokio aus Richtung Westen fährt, und das tut man am besten mit dem "bullet-train" Shinkansen, kommt man auf dem Weg nach Nagoya an "Herrn Fuji", dem Fuji-san, vorbei. Vor allem im Winterhalbjahr zeigt er öfters sein sonst an 200 Tagen des Jahres umwölktes Haupt. Vom Zug aus sieht man die Südseite, also die Vorderseite des Vulkans, der auch im Sommer das reine Weiß des Schnees trägt. Wie der Fudji oder auch der Bonsai,haben die japanischen Inseln eine Vorderseite, die Pazifikseite, und eine Rückseite. Die tonangebenden Städte, vor allem auf der Hauptinsel Honshu, liegen wie Perlen an der Schnur auf der Sonnenseite und werden vom Shinkansen in der Hauptverkehrszeit alle 7 Minuten angefahren.

Angekommen in Nagoya besteigt man den Zug einer privaten Bahngesellschaft und fährt ca. 30 km auf der Halbinsel Chita am Pazifik entlang nach Süden. Der Einfluss des nahen Ozeans ist deutlich spürbar: Auf dem Weg sieht man immer wieder Palmen und andere tropische Bäume.

Von Tokio aus erreicht man Tokoname, das sich seit der Meiji-Ära zu einem wichtigen Zentrum der Töpferei entwickelt hat, nach zweieinhalb bis drei Stunden. Wie nicht anders zu erwarten, ist der ganze Ort durch die Keramik geprägt. Das heißt, dass dort außer Bonsaischalen auch alles andere, was aus Ton herzustellen ist, produziert wird: von Wasserleitungen über Kopien italienischer Blumentöpfe bis hin zum Tanuki, dem Symboltier japanischen Erfolgswillens. Überall auf den Höfen kleiner Fabriken stapelt sich Tonware. Aber nicht nur als verkaufsfertige Produkte sieht man allenthalben Keramik. Keramische Flaschen, Ziegel, Scherben...alles wird in Häusern und Mauern verbaut. So sehen manche Straßenzüge wie ein keramisches Patchwork aus.

Wir sind allerdings nicht wegen der zum Teil pittoresken Hausarchitektur nach Tokoname gekommen. In Bonsai-Kreisen ist dieser Name natürlich ein Synonym für hochwertige Bonsaischalen. Tokoname ist auch deswegen bei uns so bekannt, weil sich hier eine rührige Vermarktungsgesellschaft gebildet hat, die den Vertrieb für ca. 50 Bonsaischalenhersteller organisiert. Diese Gesellschaft hat einen Farbkatalog herausgebracht, der auch in Deutschland erhältlich ist, und der durch die vielen Abbildungen verschiedenster Schalenformen für jeden Bonsaianer eine Quelle der Anregung ist, selbst wenn man keine Schale kaufen will.

Wir werden vom Manager am Bahnhof abgeholt und in den Betrieb gefahren. Dort treffen wir Herrn Hinagaki, der, selbst aus einer Töpferfamilie stammend, bis vor ein paar Jahren die Firma leitete. Zur Begrüßung gibt es zunächst den üblichen grünen Tee. Die ersten Minuten sind auch hier von etwas Beklommenheit begleitet, die durch die Sprachbarriere hervorgerufen. Viele Japaner verstehen zwar die englische Sprache, fühlen sich aber scheinbar etwas befangen, sich in dieser Sprache zu unterhalten. Meist verschwindet dieses Phänomen jedoch nach einiger Zeit, und eine Verständigung, wenn auch unter Zuhilfenahme von "Händen und Füßen", ist möglich. Will man aber wirklich etwas erfahren, ist ein Dolmetscher auch heute noch unerlässlich.

Der grüne Tee hilft über diese Anfangsschwierigkeiten hinweg, zumal wir ohnehin sprachlos sind, als wir in den großen "Showroom" unter dem Dach geführt werden. Hier sind alle Schalen zu finden, die man sich vorstellen kann, und auch solche, die man sich nicht vorstellen kann. Vor allem die Dimensionen einiger dieser "Töpfe" haben Ausmaße von Kinderbadewannen und Gewichte, die man gerade zu zweit bewältigt!

Aber es soll nicht nur um Superlative gehen. Es gibt alle Qualitätsstufen von einfach bis aufwendig, was sich auch in den Preisen ausdrückt. Handgemachte Mame-Schalen von 5 cm Durchmesser erreichen durchaus Preise, für die man auch eine 60 cm große, einfache Schale bekommt. Ich versuche mir in diesem Raum vor allem Farben und Strukturen einzuprägen. Die Sicherheit, mit der in jeder Schale eine harmonische Einheit von Form, Farbe,Dimension, Struktur und Verzierung erreicht wird, ist bewundernswert.

Wir sind natürlich auch nach Tokoname gekommen, um die Töpfer kennenzulernen, die diese Schalen herstellen. Herr Hinagaki hat das arrangiert, und so fahren wir zuerst in die Töpferei Yamaaki, ein Betrieb, in dem zwölf Mitarbeiter beschäftigt sind. In dieser Firma werden hochwertige Qualitäten hergestellt, die in Japan "Shosen" genannt werden. Wem bei dem Begriff Töpferei das Bild eines alten, vor sich hinwerkelnden Japaners in seiner mit abgegriffenen Werkzeugen gefüllten Werkstatthütte kommt, würde von der unromantischen Wirklichkeit enttäuscht werden. Der Betriebsleiter empfängt uns vor einer nüchternen grauen Werkshalle uns bringt uns in den ersten Stock. Im Zentrum der Halle steht der große Ofen, der, wie alles, was nicht ständig benutzt wird, von einer dicken Staubschicht bedeckt ist. Im Sommer müssen hier während des Brennvorganges enorme Temperaturen herrschen. Aber im November herrscht eine ruhige Arbeitsatmosphäre in diesem für uns undurchsichtigen Chaos aus Gipsformen, Regalwagen mit Rohschalen, Tonbatzen und Maschinen, deren Funktion man ihnen nicht ansieht. Die Menschen hier im ersten Stock stellen die Rohschalen her und bearbeiten sie bis zum Brand. Im Erdgeschoss werden sie dann glasiert, gebrannt und verschickt.

Ein Prinzip, nach dem in Tokoname Bonsaischalen hergestellt werden, basiert darauf, Tonstreifen oder Platten in Gipsform zu einer Schale zusammenzufügen.

Zuerst wird ein ca. 50 x 70 x 50 cm großer Tonklotz in 1 cm dicke Schichten geschnitten. Eine solche Tonplatte wird dann als Boden in die Gipsform gelegt. Die Wände werden aus Tonstreifen hergestellt, die ebenfalls aus solchen Platten geschnitten werden.

When departing from Tokyo to the west, which is best done by Shinkansen, the "bullet train", you will pass by Fuji-San or "Mr Fuji" on the way to Nagoya. During the winter he will be more likely to show his head without the clouds that cover him on almost 200 days during the rest of the year. From the train you can see the southern side, which is the front side of the volcano, covered by white snow well into the Summer. And like the Fuji, or like our bonsai, the Japanese islands have a front side, which is open to the Pacific Ocean, and a rear side. The most important cities, especially on the main island of Honshu, are located on the sunny side like a string of pearls, and the Shikansen connects them every 7 Minutes during the rush hours.

Once you arrive

at Nagoya, you switch to a train of a private railway company and continue for about 30 kilometres southwards down the Chita peninsula along the Pacific Ocean. Palm trees and other tropical

plants along the way are an indication of how close the ocean is.

About two and a half hours after the departure from Tokyo you will reach Tokoname, a city that, starting in the Meiji era, grew to be one of the most important centres of pottery. It will be no

surprise that the entire town is about pottery - not only bonsai pots are produced here, but everything made of clay, from water pipes and copies of Italian flower pots to the legendary Tanuki,

the Japanese symbol of success. Earthenware is stacked in every yard of the many manufactories. Ceramic bottles, bricks and tiles - everything is built into the walls and houses, which makes some

streets look like ceramic patchworks.

But it's not the picturesque architecture we are looking for; among bonsai lovers, the name Tokoname has become a synonym for high grade bonsai pots. One of the reasons for its popularity is the

existance of a very active marketing association which organizes the sales for around 50 potteries. The association also publishes a catalogue which is distributed world wide. This catalogue

showing a wide array of pot colours and shapes is a great source of inspiration for each bonsai lover, whether or not you're not you're going to actually purchase one of these pots.

The manager meets us at the train station and takes us to a factory, where we meet Mr Hinagaki, who himself comes from a potter's family and was the manager of this factory until a few years ago.

As it is custom in Japan, we are first served a welcome drink of green tea. The first minutes are a bit stiff due to the language barrier - Japanese people often speak English quite well but are

still reluctant to use it in conversation. This effect wanes after a while, and the communication starts, often using gestures and sign language. Still an interpreter will be useful if you want

to get into matters more deeply.

The green tea also helps us over the initial hesitation, but we are reduced to silence again when we are led into the large showroom under the roof. This room contains all kinds of pots that you

could imagine, and some that you couldn't - some of the pots have the size of a children's bath tub, and weights that can hardly be lifted by two people.

But we should not just focus on the extraordinary here - there are all kinds of quality levels, from the basic ones to the most elaborate and expensive ones. A hand-made mame pot of 5cm diameter

may very well reach a price level for which you would also get a more basic 60cm pot. I try to focus on the colours and structures the most - the confidence with which every pot is made into a

harmonic unity of shape, colour, size, structure and ornament is admirable.

And of course we also came to Tokoname to get to know the potters that create these pots. Mr Hinagaki already made the arrangements, and so we are first taken to the Yamaaki kiln, a factory with

twelve employees. It produces high quality pots, which are called "Shosen" in Japan. But whoever imagines an older Japanese craftsman working away in his shed filled with antique tools would be

very mistaken and maybe also disillusioned by the more prosaic reality. The factory manager receives us in an matter-of-fact, grey factory hall and leads us up to the first floor. In the centre

of the hall there is a huge kiln, which is covered with dust like everything that is not constantly in use. When it is fired during the summer, the temperatures must be unbearable. But now in

November there is a calm and busy atmosphere among the plaster moulds, rack trolleys filled with raw wares, lumps of clay and machines with inscrutable purposes. Here on the first floor, the

employees fabricate the raw pots and treat them up to the firing, on the ground floor they are glazed, fired and made ready for shipping.

In Tokoname the main technique used to create pots consists in assembling strips or slabs of clay in a plaster mould. First of all, a large piece of clay, about 50 x 70 x 50 cm, is sliced into slabs that are about 1 cm thick. One of these slabs is put into the mould as bottom of the pot, and the walls are created from strips that have been cut from the slabs.

Dann werden die Hohlräume für die Füße der Schale mit Ton gefüllt.

Then the hollow spaces for the pot's feet are filled with clay.

Diese Arbeit wird besonders sorgfältig gemacht. Als nächstes werden Wand und Boden mit einem dicken Tonstrang verbunden und verschmiert. Oben auf die Seitenwände wird ebenfalls ein Tonstrang aufgepresst, und dann alles , was über die Form hinausragt, mit einem Draht abgeschnitten. Anschließend wird eine Randschablone auf die Form gesetzt und der Rand von innen gegen die Schablone ausgeformt.

This stepis performed with special care. Then the walls and the bottom are joined together with a thick strand of clay and smudged together. The walls are finished with another strand of clay at the top. Excessive clay is cut with a wire. Then a template for the rim is put onto the mould and the rim is shaped by pressing from inside against the template.

Zum Schluss werden Wände und Boden mit einem Spachtel nachgearbeitet.

Danach ruht die Gipsform ein bis zwei Stunden. Der Gips zieht die Feuchtigkeit aus dem Ton, und die Schale lässt sich leicht aus der Form lösen. Von innen abgestützt, wird die Schale gestürzt und zum Trocknen weggestellt.

Finally the walls and the floor are finished with a putty knife.

After that, themould rests for one to two hours, during which the plaster extracts humidity from the clay, making it easier to remove the clay from the mould. With additional support from the inside, the pot is removed and put away for drying.

Die Gipsformen können dann erneut benutzt werden, jedoch nur maximal einen Tag, denn dann sind sie zu feucht und müssen eine Zeit trocknen.

Die Rohschale wird etwas später, wenn sie leicht angetrocknet ist, nachgearbeitet.

After that the plaster moulds can be reused, but at most for one day until they become too moist and need to be left to dry again for a certain period.

When it has dried for a while, the raw pot is being refined.

Der Ton, der hier verarbeitet wird, stammt zum Teil aus Shigaraki und auch von der Insel Kiushu. Auch in Tokoname gab es früher große Tonvorkommen, daher auch diese Entwicklung. Heute kann der Bedarf mit hiesigem Ton nicht mehr gedeckt werden. Der gelbe Ton von Kiushu bekommt nach dem Brand eine graue Farbe, der lederfarbene Ton aus Shigaraki wird dunkelbraun. Die Tone schrumpfen im Verarbeitungsprozess um 13%. Man benötigt also eine 69 cm -Form, um nach dem Brennen eine Schale von 60 cm zu haben.

The clay which is processed here comes in parts from Shigaraki, in parts from the Kiushu island. Tokoname itself used to have large clay deposits, which is why the development started here in the first place, but today the demand can no longer be met with local clay. The yellow clay from Kishu turns grey after firing, and the leather-coloured clay from Shigaraki turns dark brown. During processing the clay shrinks by around 13%, so to obtain a pot of 60 cm after firing, a mould of 69 cm should be used.

Wenn der Ton lederhart ist, werden mit einer Art Plätzchenform die Löcher aus dem Boden ausgestochen, das Siegel angebracht und die Schale ein letztes Mal fein bearbeitet.

Unglasierte, vor allem kleinere Schalen, werden nur einmal gebrannt. Die größeren der unglasierten Schalen und die, die glasiert werden sollen, werden bei ca. 800° C vorgebrannt (Schrühbrand).

When the clay is leather hard, the holes in the bottom are cut with a device similar to a cookie cutter. The potter's mark is added and the pot is refined for a last time.

Unglazed and particularly small pots are only fired once. The larger unglazed pots and the glazed ones are fired for the first time at around 800°C (bisque firing).

Der Glattbrand (1200° C) lässt dann erst die schönen Farben der Glasuren entstehen. Der Ofen wird mit Gas geheizt und ist so groß, dass er mit Regalwagen beschickt werden kann.

The final firing at 1200°C then brings out the great colours in the glazes. The kiln is fired with gas and is large enough to be loaded with rack trolleys.

Insgesamt zerbrechen 20% der Schalen während des Herstellungsprozesses.

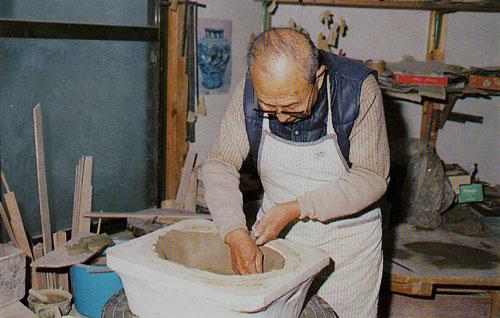

Nach diesem Einblick in die Details der Schalenherstellung lernen wir noch einen kleinen Familienbetrieb kennen. Auch hier wird so produziert, wie es oben beschrieben ist. Viel Wert insbesondere auf die detailgenaue Ausarbeitung gelegt. Besonders komplizierte Schalenformen können deshalb, trotz Gipsformen, nur unter großem Zeitaufwand hergestellt werden. Der Seniorchef und seine Frau sind damit beschäftigt und hinterlassen bei uns doch noch einen kleinen Eindruck von Romantik.

Altogether, about 20% of the pots crack during production.

After these insightsinto the details of pot making, we were introduced to another factory, a smaller family business. The general way of production is the same as described above. Much effort is put into the detailed finishing. This is why the fabrication of more complicated shapes is very time consuming, even with the plaster moulds. The senior principal and his wife are busy with this work, and this provides us at least with a glimpse of a more romantic image of pottery.

Auf der Rückfahrt nach Tokio sind wir noch ganz angetan von den freundlichen Menschen, denen man anmerkt, dass sie stolz auf ihre Arbeit sind. Es ist zwar ein Massenprodukt, aber man kann sehen, dass jede Schale die volle Aufmerksamkeit des Menschen bekommt, der sie herstellt. Mir scheint das ein Grund des Erfolges von Tokoname-Bonsaischalen zu sein.

During our return to Tokyo we are still impressed by the kindness of the people and the sense of pride that they take in their work. Even though they are a mass product, one can see that every pot is given the undivided attention of the person working on it. It seems to me that this is one of the reasons for the success of Tokoname bonsai pots.

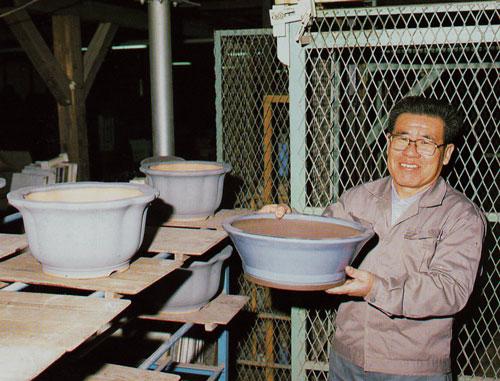

Glasierte Schalen vor und nach dem Brand.

Glazed pots before and after firing.

Text: Michael Exner

Fotos / Photographs: Michael Kros

Dieser Artikel wurde freundlicherweise von BONSAI ARTzur Verfügung gestellt.

Our sincere thanks to BONSAI ARTfor kindly granting the permission to publish this article.

Translation: Stefan Ulrich